Drug Court House is far removed from the court rooms at the nearby Dandenong Magistrates’ Court.

The offices on Lonsdale Street Dandenong glow with photos of successful participants, each shaking the hand of Magistrate Gerard Bryant as they receive medals of achievement.

Their paintings created in their art therapy classes also decorate the walls. Brimming with optimism and brightness, these arts were produced by serious offenders with entrenched drug habits.

And the tight-knit team of case workers, clinicians, office staff, a Victoria Legal Aid lawyer and Mr Bryant are proud to tell you their story.

It’s a program – despite a wide suite of services – that is less costly than prison. And it delivers lower re-offending rates.

“It’s being smart on crime,” Mr Bryant says.

He says participants look forward to coming to Drug Court House, where the “wraparound” and holistic services support their rehabilitation.

They’re not punished for relapsing into drug use – as it is part of addiction. But they are expected to be honest about it and to keep all of their appointments.

It can be hard work at first. Many are institutionalized by long stints in prison. Breaking away from their old friendship group of criminals and drug users is isolating.

Just making all the appointments in a week can be a challenge.

But the team is ready to address the underlying causes – the mental illness, past traumas, as well as helping rebuild family connection and making positive friends.

Even after they’ve successfully completed the program, the clients are welcome to stay in touch. Some even do so after their orders have been cancelled.

In prisons, inmates are even praising the program. “They say it’s a good program but it’s a tough program,” Mr Bryant says.

“To a man they feel supported.”

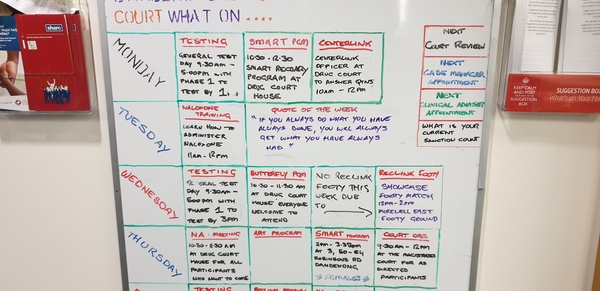

The whiteboard is a full Monday-Friday schedule of appointments for the participants.

Their week includes three urine screenings, a review with Mr Bryant at Dandenong Magistrates’ Court as well as services to rebuild their lives.

The services offered include art therapy, cooking, anger management, parenting programs, literacy assessments, employment and life-skills services, drug rehab and counselling, Narcotics Anonymous, Wednesday footy at Noble Park Football Club and Friday barbecues.

A participant told the court that there was so much to do, there was no time to play up.

“Each of the therapeutic response services are tailored for each individual,” Mr Bryant said.

“I think the experiences that a lot of offenders have had on other orders haven’t felt as supported as much as they need.”

The program’s “jewel-in-the-crown” is its 30 properties – assigned to accommodate its participants. It’s a rare feature, compared to drug courts around the world.

It breaks the cycle of walking from prison to a stay at a boarding house with criminals and drug users.

The court has a capacity of 60 participants, with a three-month waiting list. This gives the court some discretion in selecting offenders willing to take advantage of the opportunity.

The more informal court differs from regular courts. Those who progress earn rewards – they are praised and applauded, and given the chance to spin a big wheel for prizes.

A magistrate for 12 years, Mr Bryant says the drug court has been his most satisfying, rewarding work.

“For me it wasn’t philosophically a huge shift. I’ve always been interested in tackling the underlying causes of offending.

“You cannot arrest your way out of the problems that the criminal justice system faces alone.”

He sees his clients each week for up to two years. He learns the names of their family, even their pets.

“You get to travel with someone on the journey. It can be a frustrating experience but also a wonderful experience.

“There are some really special moments. It can be quite emotional.

“We allow them to reinvent themselves.”