“It’s like living in an open prison.”

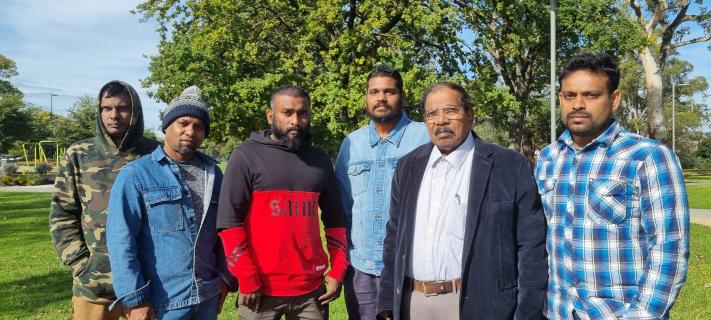

Sathees is one of five Tamil asylum seekers in Melbourne’s South East who has spoken out to Star News.

The men are among a seemingly ‘forgotten’ cohort of asylum seekers in Australia.

They have been in Australia for more than a decade. Their applications to settle here are in a seemingly endless review.

Sathees and the other four are in their thirties, and should be in the prime of their lives.

But instead they are ekeing an existence with little income, living in crowded share-houses and even garages with no heating, and without basic privileges such as Medicare.

“You don’t have any freedoms,” Sathees says.

“You are under detention even when you are out. You can’t decide what you’re doing in the future because the Government and Immigration is holding it up.

“They are torturing.”

In February, the Federal Government announced a permanent visa pathway for more than 19,000 holders of Temporary Protection Visas and Safe Haven Enterprise Visas, a department spokesperson said.

It was welcome news for temporary visa holders, many of whom are Sri Lankan (2223).

But another 1657 applicants are still being processed or reviewed in courts – nearly half of which are in Victoria.

Among them, the second-highest cohort are Sri Lankan (245), only behind Iran (519). Most of the Sri Lankans are believed to be in the South East.

One of the men Nige says: “After Covid, everything has got expensive. Only a few people can survive like this.

“So many young men have heart attacks. At 30-35 years old, they’re depressed, alcoholic and stressed. They suicide or harm themselves because they don’t know and it’s hard to survive.

“When people hear our stories, they are shocked.”

Nige fled by boat in 2009, leaving behind his wife and three-year-old son. He’s desperate for a permanent visa in the hope of reuniting with his family – heartbreakingly, he hasn’t since seen his now 17-year-old son except via video calls.

He spent six years in detention at Christmas Island, Villawood and Maribyrnong. As part of a “cruel” detention, he was “caged” in what felt like a “shoebox”, fed the same food that after a time he couldn’t bear to eat.

“We don’t know when we will be released – we can’t do anything, we don’t know anything You can’t imagine what they were going to say in Canberra.”

Other friends declined into depression, exploded into screaming, self-harmed and took their lives. Some were detained for up to 10 years.

On his release, he’s applied and re-applied for a series of temporary visas for the past seven years. Some friends who came by boat have got permanent visas, while others languish like him for no apparent reason.

Others were welcome in Australia on working visas while asylum seekers are shunted aside.

“It’s a bull-s*** process.

“I feel confused where I am – same as in the detention centre.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s ‘blue’ or ‘red’ in Government, the policy is the same. Everyone kicks you like a political football.

“Australia is a democratic country. I don’t know why they treat us like this.

“We are human.”

The Government’s stated policy remains that people travelling illegally by boat won’t be allowed to settle permanently in Australia.

The policy has successfully stymied the flow of ‘unauthorised maritime arrivals’ to Australia, disrupted people smuggling and prevented loss of lives at sea, according to the Government.

On the other hand, Australia’s policy is not to return people to countries where they face persecution and a real risk of torture, persecution or death.

Justice and Freedom for Refugees chair Wicki Wickiramasingham has been a refugee advocate for nearly 30 years.

A long-serving ALP member and branch leader, he says he must speak out.

Since October, he knows of six asylum seekers who took their own lives.

“Some of them didn’t have visas, some on bridging visas with no work permit and didn’t want to tell anyone. They were struggling but suffering in themselves.”

“They don’t come here for the good life. They are working hard, they spent 40 days on the sea – and if the boat sinks they lose their life.”

He said Tamils seem to be less successful in gaining permanent visas than other backgrounds, noting the close relationship between Australia and the Sri Lankan government.

One of the group Lenny tells about leaving behind his girlfriend and parents in Sri Lanka more than a decade ago.

His parents have now passed away. And his partner could wait for him no longer and married another man.

During that time, he says he has worked legally and paid tax. He followed the visa application process, but his submission was botched by a lawyer that he paid $6300 and has also been rejected by an Immigration Minister.

He says he can’t sleep properly due to the worry. “I don’t want a life like this.”

Roger fled from Sri Lanka by boat more than 10 years ago. His application for a permanent protection visa was rejected.

In 2016, he lodged an appeal to the Federal Court. With no money for a lawyer, his case is still yet to be heard.

In his sharehouse of five Tamil asylum seekers, three have gained permanent visas, two have missed out.

The Government expects 19,600 eligible asylum seekers to receive a Resolution of Status visa by early 2024.