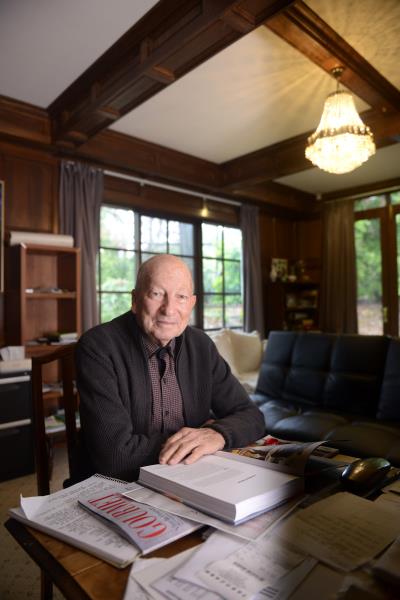

Journal columnist Jack Johnson is the son of a World War I veteran. In this special commemorative edition Jack writes “with love to our dad“ Frederick Herbert Johnson, 6th Battalion, AIF.

WE WERE four children born in the late 1920s and I was the third child, born in 1929. We were children of a T.P.I (permanently and totally incapacitated) soldier, one of the Anzacs of the Great War, 1914-1918.

Dad was partly paralysed on his left side, with many internal injuries, from a shell burst on the Western Front in August 1918.

His war record states that he suffered a gunshot wound to the neck and a fractured spine.

Despite this he did not receive a full pension until 18 years after he was disabled in France.

After returning to Australia, Dad spent almost five years in a repatriation hospital in Caulfield.

For much of this time he was flat on his back in one of those wheeled stretcher beds, with an angled mirror above his head so he could see a little of what was around him.

He was forever grateful to the doctors and nurses who put his broken body back together.

After much surgery, they taught him to stand up again and walk and be fully normal.

Mum’s older sister was a nurse at the hospital, and mum used to go there on weekends to help look after the wounded soldiers.

This is where our mother, Mary Doherty, met and fell in love with Dad.

They were married a few years after he was finally discharged from the hospital.

Mum told me that when she told her family and friends she was going to marry Dad, that many of them disapproved, some saying to her, “but you can’t marry him, he is a cripple“.

Dad never talked about the war to us children. As I think the horrors and trauma to a county boy who was still in his teenage years when he joined the Great War, was such that he could not bring himself to speak of it to his young, innocent children.

He would only ever joke about the war with us kids.

He used to tell us he still had so much shrapnel in his body and a couple of metal plates in his skull, that we should be careful when were at the table playing with our magnets.

He also used to tell us that he had more stitches down his spine than there were in a chaff bag.

We lived at 88 McCrae Street and the rent on the house was exactly the same as Dad’s pension.

The pension situation meant Dad had to get a job. In 1926 he became a traffic officer at the stock and produce market.

Dad would have to go to the old town hall to get paid.

Sometimes he would take a couple of us kids with him to Mr McAlpine’s office.

He was a nice man and always made a fuss over us because he thought Dad was quite special.

The first time I remember going to the town hall with Dad he showed us the honour roll boards, some of the names were friends and fellow soldiers.

After the Second World War, we were old enough to go into the town hall without Dad, and read the names on the new honour roll board.

Sadly, two of them were childhood friends and neighbours.

One thing that gave me a proud feeling at a very young age, on being the child of a TPI serviceman of the Great War, was the great respect and gratitude shown to these returned or deceased service men by the community of Dandenong.

Dad was finally given a full TPI pension in about 1936. That was when what we kids called the “golden years“ began.

We began to get new clothes and shoes. Dad was given a gold pass on the Victorian railways, this meant lots of trips into Melbourne for Dad and us boys.

In late 1938 we went to Victoria Barracks in St Kilda Road. We were quite impressed with the large guns outside the front entrance. We were treated as very special kids because of who our Dad was.

They were good men, many of them of high rank, and as I grew older and thought of these soldiers, I wondered if any of them had the slightest inkling that in little over a year Australia would be entering a second world war with Germany.

My parents shared a long happy life together.

Dad died at 80 due to war injuries and mum died at 87.