By CHAD VAN ESTROP

In Maryam Wafajo’s former life, school was a place of arbitrary and random violence dispensed by impatient and intolerant instructors. At school in her native Pakistan teachers would routinely pepper student’s knuckles with rulers, sticks or whatever came to hand.

The reasons for this violence were trivial enough: for speaking out of turn, or for a lapse in concentration, or for failing to complete homework. Sometimes the reason was not at all clear.

Intolerance in the classroom was only half the story. The trip to school was along streets patrolled by radical Taliban on motorbikes warning people not to attend school. They threatened violence and kidnapping against those who defied them.

At Noble Park English Language School — where Ms Wafajo is now a pupil — life is very different and truly a world apart.

Noble Park is one of four schools in Victoria that offers new arrivals to the country a six-to-12-month crash course in English.

The school’s population is fluid and as of late last month 512 students — mainly from Afghanistan — were enrolled at four campuses.

English language schools offer places to school-aged children who are migrants, refugees or asylum seekers. Eligible students have usually lived in Australia for less than six months. The schools are a pathway to mainstream education.

“We are a place that assists students in their transition into a new country both in terms of cultural awareness and language proficiency,” says the principal at Noble Park, Enza Calabro.

She says the school’s program is continually tweaked to adjust to the needs of particular groups.

During a recent wave of Sudanese arrivals, Ms Calabro says a teacher was used to take students to and from school.

“These students had come from a non-industrialised country and did not know how to use a train or bus.”

Born in Pakistan and of Hazara heritage, Ms Wafajo says the workload at her school back home was tiresome, with up to 14 subjects a year forced onto students as young as 14.

Ms Wafajo, 18, says the punitive approach to teaching made learning difficult.

“In Pakistan the teachers get angry when students ask a lot of questions,” she says in haltering and strongly accented English.

The fear Ms Wafajo encountered at school was compounded by the anti-education messages of the Taliban. “Sometimes I would just sit at home because I was scared.”

The persecution of Hazara people like Ms Wafajo’s family dates back to the 16th century. The Hazaras are targeted by Afghanistan’s major ethnic groups — the Sunni muslims and the Pashtuns — on religious grounds.

The plight of the Hazara people in Afghanistan has improved slightly since the ousting of the Taliban government in 2001, according to the United Nations. But they continue to be victimised in neighbouring Pakistan.

Amnesty International has recorded 91 separate attacks on Hazaras in Pakistan since January 2012, resulting in more than 500 deaths.

Ms Wafajo, who arrived in Australia by boat in late 2011, now has a stable education platform after 11 months at Noble Park.

“I feel comfortable to ask teachers questions now. I know they will take time to give me help. I’m so thankful to my teachers.”

At the Blackburn English Language School in Croydon North, student names like Dawt-Kuu, Mawi-Mawi, Suah-Pi, Bawi-Phir dominate.

The student population at English language schools is a barometer of world conflict. Once the student body was dominated with Sudanese refugees.

Now pupils from Afghanistan and Burma are the mainstay.

A teacher at Blackburn, Carly Minett, has witnessed the transformation of many pupils, having taught in English language schools since 2005.

“You have the opportunity to help people at a time when they are at their most vulnerable and that’s pleasing,” she said.

Ms Minett understands the importance of providing support to new arrivals, as her grandparents struggled to adjust when they migrated to Australia from Italy in the 1930s.

“When my family first came to Australia they didn’t have much support, so it is nice to be able to help people that have chosen Australia as their home.”

But Ms Minett said her role is not without its challenges: “You always have to decode and understand where somebody has come from and how it affects their perspective.”

Principal at Blackburn, Robert Colla, said the turnover of students at his school is brisk.

As of last month the school had no enrolments for second term next year.

Mr Colla said the school focuses on bringing its 340 pupils — currently mostly Burmese — up to mainstream standards in reading, writing and awareness of Australian culture.

“We are the starting point for creating an environment for students so they can go off and learn.

“[English language schools] are a central focal point for newly arrived children, not just for education but for the provision of services as well.”

For pupils the schools act as an interconnected support system.

At Blackburn nurses specialising in refugee health visit fortnightly, welfare workers monitor student behaviour, interpreters assist with monthly parent-teacher interviews and transition officers help place graduating students into mainstream schools.

At classroom level, instructions are delivered slowly and the lines between English and other lessons are blurred. Reminders of correct tenses and sentence constructions can sporadically interrupt an algebra lesson.

Teachers are qualified to teach English to non-native speakers.

Bilingual aides — particularly in the lower grades — provide an important “link” between teachers and students.

The importance of the teaching aides is underlined by the fact that about one-third of students have suffered some disruption, or interruption to their schooling at some stage in their lives.

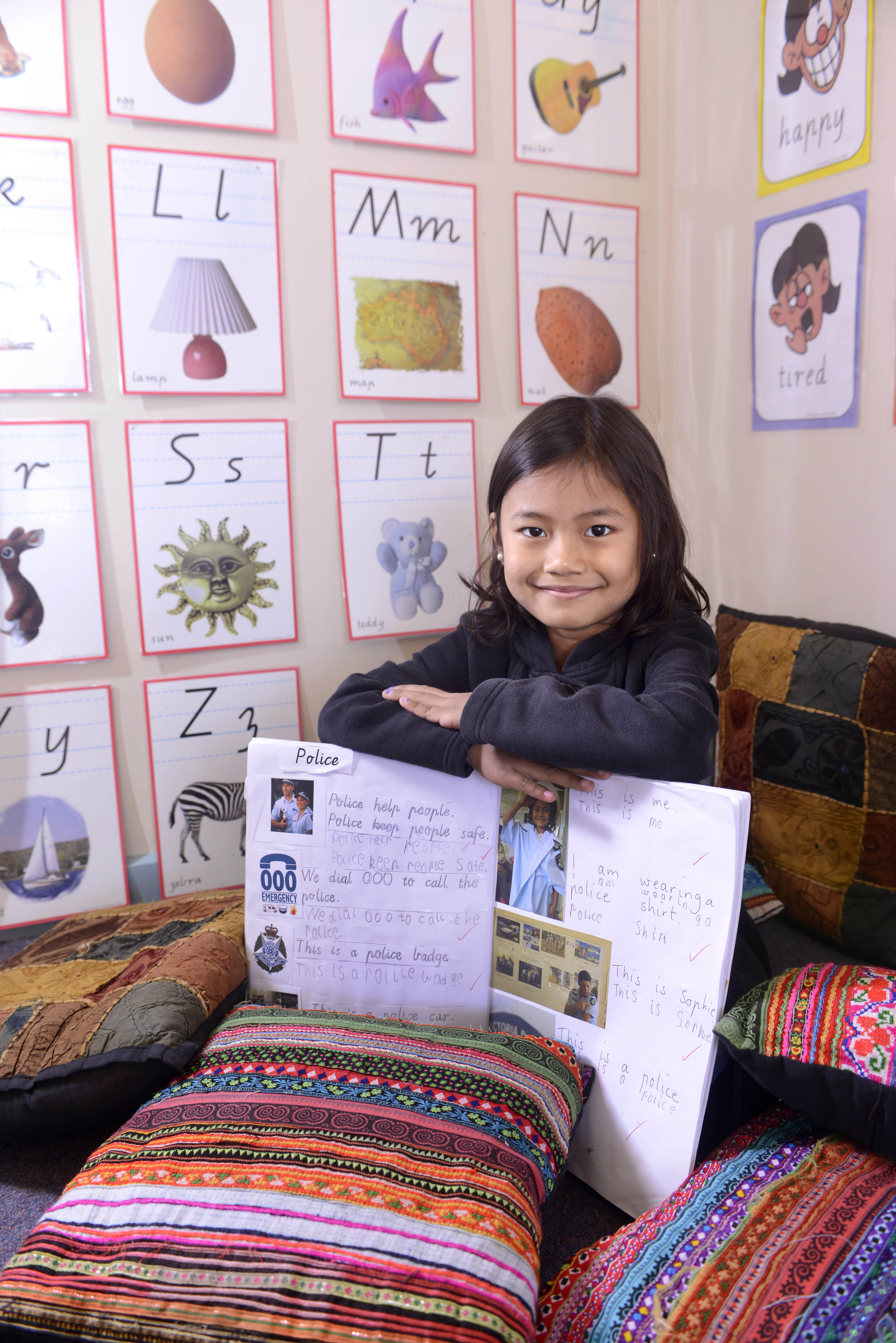

Class sizes are deliberately small and simplified classroom activities mimic mainstream schooling.

The primary curriculum includes units on emergency services, transport and wildlife with an emphasis on speaking and reading about what is learnt.

The secondary curriculum varies dependant on a student’s proficiency. Some have to be taught how to hold a pen while others craft argumentative essays at will.

Ms Wafajo says coming to Australia has given her life purpose. Propaganda against education and the fear of the ruler no longer haunt her. She is adjusting to a different culture.

“In Afghanistan as soon as girls turn 18 they get married and there isn’t much opportunity to learn — it is so different here.”

Ms Wafajo will graduate from Noble Park this month and hopes to study nursing. “I really like to help people and solve their problems.”

What do you think? Post a comment below.