By LACHLAN MOORHEAD

WHEN Ford announced over summer that it would cut 300 jobs from its manufacturing plants in Geelong and Broadmeadows, Doveton-bred Dennis Glover felt history repeating itself.

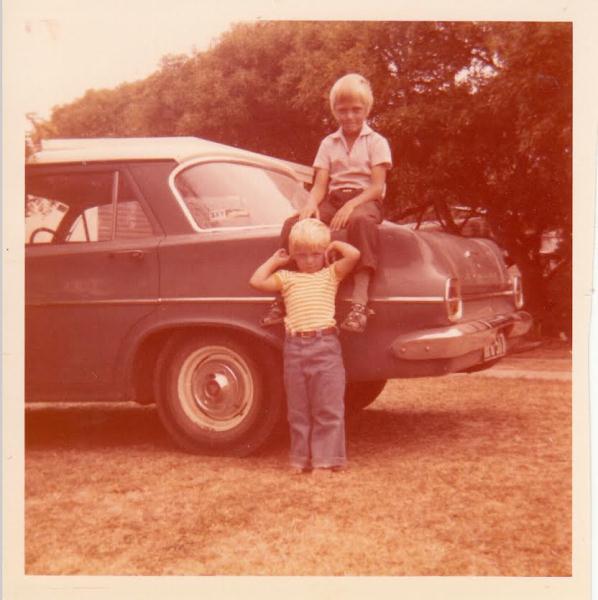

It was during a visit to his old suburb last year that the Labor speechwriter was reminded of how different his childhood home, Doveton, appeared compared to the thriving manufacturing hub his Irish father, Rodney, had been a devoted contributor to throughout the 1970s and early ’80s, while working for International Harvester and then General Motors Holden.

“I came to Doveton for a family birthday just before Christmas last year and had a look around and was shocked by the deterioration,” Dennis said.

“I made a point of driving through my old street and was shocked by how bad it looked physically, then over the summer when it was announced that the car plants were closing in Geelong and elsewhere, I thought haven’t they learnt?

“If they go to places like Doveton they’ll see this is a big mistake. I rose in a fit of real anger at the real short-sightedness of the policy.”

Dennis, who went to school with Dandenong MP John Pandazopoulos, was moved to write an article for The Age in February where he traversed the Doveton of his childhood with the suburb’s 2014 incarnation, under the headline ’Working class dreams fade as jobs dry up’.

The article will form the basis of a book Dennis said he planned to write over summer detailing Doveton’s manufacturing decline.

In the piece Dennis recalled Doveton’s hard-working and highly unionised industrial belt near the Prince Mark Hotel, where thousands of people streamed in and out of factories when the siren sounded at 8am.

“Now it’s just a trickle,” Dennis said.

The fall of Doveton’s manufacturing sector began in the mid-1980s, the beginning of a domino effect which saw the suburb’s schools and other industries also hit hard, according to Dennis.

“Doveton was on the upswing from the mid to late 1950s, when all the big major investments in power plants and truck plants took off, then housing commission houses were built in the early ’50s,” he said.

“It was a serious working class neighbourhood and a tough place to grow up but not frightening or threatening.

“From the late 1970s manufacturing industries across the nation went into a bit of a decline, working class standards started to fall and big companies started laying people off. By the mid-1980s, Doveton was a deprived area and it’s gotten worse since.”

When the economy changed, Dennis said, governments didn’t put enough effort into replacing jobs.

“In a sense there’s an obsession with efficiency and productivity and not with people,” he said.

“It’s okay to say we need to cut taxes and lower wages to make the economy more productive but that doesn’t improve the lives of people.”

“When factories close in manufacturing suburbs like Doveton it isn’t just the factory closing, you end up with knock-on effects for local shops, people don’t move in, clothes stores go into decline,” he said.

Dennis called on “gutsy” political leaders who were passionate about Doveton to assert active change in the suburb.

“The area needs leadership, it needs gutsy young politicians to go in and pull the place up by its bootstraps,” he said.